C++ Read Text Files Unknown Name I/o Redirect

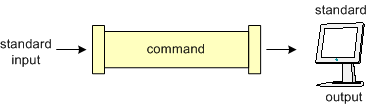

In typical Unix installations, commands are entered at the keyboard and output resulting from these commands is displayed on the calculator screen. Thus, input (by default) comes from the last and the resulting output (stream) is displayed on (or directed to) the monitor. Commands typically go their input from a source referred to equally standard input (stdin) and typically display their output to a destination referred to as standard output (stdout) as pictured below:

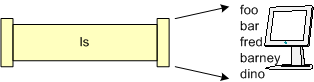

Equally depicted in the diagram to a higher place, input flows (by default) as a stream of bytes from standard input along a aqueduct, is then manipulated (or generated) by the command, and command output is and so directed to the standard output. The ls command can and then exist described equally follows; there is really no input (other than the command itself) and the ls command produces output which flows to the destination of stdout (the terminal screen), as beneath:

The notations of standard input and standard output are actually implemented in Unix every bit files (as are most things) and referenced by integer file descriptors (or aqueduct descriptors). The file descriptor for standard input is 0 (cypher) and the file descriptor for standard output is 1. These are not seen in ordinary use since these are the default values.

Input/Output Redirection

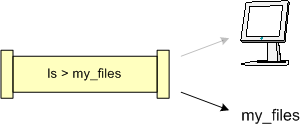

Unix provides the capability to change where standard input comes from, or where output goes using a concept called Input/Output (I/O) redirection. I/O redirection is accomplished using a redirection operator which allows the user to specify the input or output data be redirected to (or from) a file. Note that redirection e'er results in the data stream going to or coming from a file (the terminal is also considered a file).The simplest case to demonstrate this is bones output redirection. The output redirection operator is the > (greater than) symbol, and the general syntax looks as follows:

command > output_file_specSpaces around the redirection operator are not mandatory, but practise add readability to the command. Thus in our ls example from in a higher place, we can observe the following use of output redirection:

$ ls > my_files [Enter] $Notice at that place is no output actualization afterward the command, only the render of the prompt. Why is this, you lot ask? This is because all output from this control was redirected to the file my_files. Observe in the post-obit diagram, no data goes to the last screen, but to the file instead.

Examining the file as follows results in the contents of the my_files being displayed:

$ true cat my_files [Enter] fooIn this example, if the file my_files does not exist, the redirection operator causes its creation, and if it does exist, the contents are overwritten. Consider the example below:

bar

fred

barney

dino $

$ echo "Hullo Earth!" > my_files [Enter] $ true cat my_files [Enter] Howdy Globe!Observe here that the previous contents of the my_files file are gone, and are replaced with the string "Hello World!"

$ cat my_files [Enter] Howdy Globe! $ true cat my_files > my_files [Enter] $ true cat my_files [Enter] $

Often nosotros wish to add together data to an existing file, so the shell provides united states of america with the capability to append output to files. The append operator is the >>. Thus we tin do the following:

$ ls > my_files [Enter] $ repeat "Hullo World!" >> my_files [Enter] $ cat my_files [Enter] fooThe first output redirection creates the file if it does non exist, or overwrites its contents if it does, and the second redirection appends the string "Hullo World!" to the end of the file. When using the append redirection operator, if the file does not exist, >> will crusade its creation and append the output (to the empty file).

bar

fred

barney

dino

Hello World!

The ability also exists to redirect the standard input using the input redirection operator, the < (less than) symbol. Annotation the point of the operator implies the management. The general syntax of input redirection looks every bit follows:

control < input_file_specLooking in more than item at this, we volition utilize the wc (westwardord count) control. The wc command counts the number of lines, words and bytes in a file. Thus if we practice the post-obit using the file created above, we see:

$ wc my_files [Enter] 6 seven 39 my_files where the output indicates 6 lines, 7 words and 39 bytes, followed by the proper noun of the file wc opened.We can also apply wc in conjunction with input redirection as follows:

$ wc < my_files [Enter] 6 7 39 Annotation here that the numeric values are as in the example above, but with input redirection, the file proper name is not listed. This is because the wc control does not know the name of the file, just that information technology received a stream of bytes to count.Someone will certainly ask if input redirection and output redirection can be combined, and the answer is near definitely yes. They tin be combined as follows:

$ wc < my_files > wc_output [Enter] $At that place is no output sent to the terminal screen since all output was sent to the file wc_output. If we then looked at the contents of wc_output, it would comprise the same data as above.

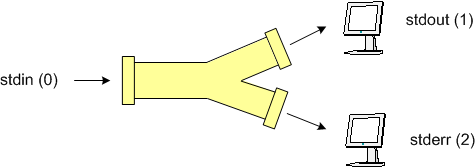

To this bespeak, we have discussed the standard input stream (descriptor 0) and the standard output stream (descriptor 1). There is some other output stream called standard error (stderr) which has file descriptor 2. Typically when programs return errors, they return these using the standard error channel. Both stdout and stderr straight output to the final by default, and then distinguishing between the ii may exist difficult. However each of these output channels can be redirected independently. Refer to the diagram below:

The standard error redirection operator is similar to the stdout redirection operator and is the 2> (two followed by the greater than, with no spaces) symbol, and the general syntax looks as follows:

command 2> output_file_specThus to show an example, nosotros observe the following:

$ ls foo bar 2> error_file [Enter] foo $ true cat error_file [Enter] ls: bar: No such file or directoryNotation here that but the standard output appears one time the standard mistake stream is redirected into the file named error_file, and when nosotros display the contents of error_file, it contains what was previously displayed on the termimal. To show another example:

$ ls foo bar > foo_file 2> error_file [Enter] $ $ cat foo_file [Enter] foo $ true cat error_file [Enter] ls: bar: No such file or directoryIn this instance both stdout and stderr were redirected to file, thus no output was sent to the terminal. The contents of each output file was what was previously displayed on the screen.

Note there are numerous ways to combine input, output and error redirection.

Another relevant topic that claim discussion hither is the special file named /dev/aught (sometimes referred to as the "bit bucket"). This virtual device discards all data written to it, and returns an End of File (EOF) to any process that reads from it. I informally describe this file equally a "garbage can/recycle bin" like affair, except there's no lesser to it. This implies that information technology tin never make full upwardly, and nada sent to it can ever be retrieved. This file is used in place of an output redirection file specification, when the redirected stream is not desired. For example, if you never intendance about viewing the standard output, just the standard error channel, you can practise the following:

$ ls foo bar > /dev/null [Enter] ls: bar: No such file or directory In this case, successful command output will be discarded. The /dev/zilch file is typically used as an empty destination in such cases where in that location is a large volume of inapplicable output, or cases where errors are handled internally so mistake letters are not warranted.One last miscellaneous item is the technique of combining the two output streams into a single file. This is typically done with the 2>&i control, as follows:

$ command > /dev/null 2>&1 [Enter] $Here the leftmost redirection operator (>) sends stdout to /dev/nada and the ii>&i indicates that channel 2 should be redirected to the same location equally aqueduct 1, thus no output is returned to the final.

Redirection Summary

| Redirection Operator | Resulting Performance |

|---|---|

| command > file | stdout written to file, overwriting if file exists |

| command >> file | stdout written to file, appending if file exists |

| command < file | input read from file |

| command two> file | stderr written to file, overwriting if file exsits |

| control two>> file | stderr written to file, appending if file exists |

| command > file 2>&ane | stdout written to file, stderr written to same file descriptor |

Pipe Operator

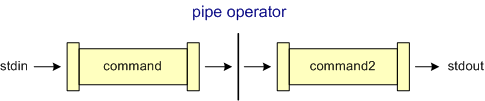

A concept closely related to I/O redirection is the concept of pipe and the pipe operator. The pipage operator is the | graphic symbol (typically located in a higher place the enter key). This operator serves to bring together the standard output stream from one process to the standard input stream of another procedure in the following style:Nosotros can wait at an example of pipes using the who and the wc commands. Recall that the who command will list each user logged into a motorcar, i per line as follows:

$ who [Enter] mthomas pts/two Oct 1 13:07 fflintstone pts/12 Oct 1 12:07 wflintstone pts/four October one 13:37 brubble pts/6 October 1 13:03 Likewise recall that the wc command counts characters, words and lines. Thus if we connect the standard output from the who control to the standard input of the wc (using the -fifty (ell) option), we can count the number of users on the organisation: $ who | wc -l [Enter] 4 In the first part of this example, each of the four lines from the who command will be "piped" into the wc command, where the -l (ell) option will enable the wc command to count the number of lines. While this example simply uses 2 commands continued through a unmarried piping operator, many commands can exist connected via multiple piping operators.

Filters Are Our Friends

Closely related to pipes and the pipe operator is the topic of filters. Filters are commands that modify data passed through them, typically via pipes. Some filters tin exist used on their ain (without pipes), but the true power to manipulate streams of information to the desired output comes from the combination of pipes and filters. Summarized beneath are some of the more than useful Unix filters.head/tail

Two straightforward commands which are ofttimes used every bit filters are the head and tail commands. When used with file specifications, these two commands display the start or final ten lines (past default) of a file, as follows:

$ head /etc/passwd [Enter] root:x:0:0:root:/root:/bin/bash bin:x:1:1:bin:/bin:/sbin/nologin daemon:ten:two:2:daemon:/sbin:/sbin/nologin adm:10:3:iv:adm:/var/adm:/sbin/nologin lp:10:iv:7:lp:/var/spool/lpd:/sbin/nologin sync:10:5:0:sync:/sbin:/bin/sync shutdown:x:six:0:shutdown:/sbin:/sbin/shutdown halt:x:7:0:halt:/sbin:/sbin/halt mail:ten:8:12:post:/var/spool/mail:/sbin/nologin news:x:ix:13:news:/var/spool/news: In the to a higher place example, we only encounter the first ten lines of the /etc/passwd file. However, if nosotros wanted to see a listing of the x oldest files in a directory, we could do the following: $ ls -tl | tail [Enter] -rw-r--r-- ane root root 315 Jun 24 2001 odbcinst.ini -rw-r--r-- 1 root root 1913 Jun 24 2001 mtools.conf -rw------- 1 root root 114 Jun 13 2001 securetty -rw-r--r-- 1 root root 1229 May 21 2001 bashrc -rw-r--r-- 1 root root 17 Jul 23 2000 host.conf drwxr-xr-x 2 root root 4096 May 15 2000 opt -rw-r--r-- 1 root root 0 Jan 12 2000 exports -rw-r--r-- 1 root root 161 Jan 12 2000 hosts.allow -rw-r--r-- 1 root root 347 Jan 12 2000 hosts.deny -rw-r--r-- 1 root root 0 Jan 12 2000 motd In this example, the ls control is used with the t and l (ell) options; the t selection sorts by modification fourth dimension and the 50 (ell) option results in a long list format. This output is and then piped through the tail filter, which just displays the last ten lines, that is the ten oldest files.cutting

The cut command provides the capability to vertically piece through each line of a file based upon character or field positions. When used with the -c (to specify grapheme) option equally follows:

cut -cstart_pos-end_pos < input_filethe cutting control extracts (and keeps) characters in positions start_pos through end_pos (inclusive), discarding the rest of the line. The start_pos and end_pos are integer values ranging between one and the length of the line. For instance, if we wish to select only the username of each user currently logged into our system, we could do the following:

$ who | cut -c1-12 [Enter] mthomasThis example pipes the output from the who control into the cut command, where the characters one through twelve are cut (and directed to stdout by default) while all other characters on each line are discarded.

fflintstone

wflintstone

brubble

If 1 wishes to cut from a starting character position to the end of the line, the end position is omitted every bit follows:

cut -cstart_pos- < input_fileUsers tin also cut based upon "fields" of data past using the -f and (mayhap) the -d options. Refer to man pages for additional details.

tr

The translate command provides the ability to translate characters coming from the standard input and directed to the standard output. General syntax for this command is:

tr set1 set2 < stdinwhere each individual character in set1 is translated to their matching positional character in set2. A common usage of the translate filter is translating a string of characters to upper (or lower) case. Examine the post-obit instance:

$ who | cut -c1-12 | tr '[a-z]' '[A-Z]' [Enter] MTHOMASIn this extension of an earlier example, the who command is piped into cut, where the first 12 characters are cut from each line. These twelve characters are and so piped into the translate command where each lower case character is translated to their matching upper case counterpart. Unless redirection occurs, output is written by default to standard output.

FFLINTSTONE

WFLINTSTONE

BRUBBLE

sort

The sort command behaves exactly every bit one might expect, that is, it sorts data directed to information technology. Thus nosotros tin can modify our example from in a higher place every bit follows:

$ who | cut -c1-12 | tr '[a-z]' '[A-Z]' | sort [Enter] BRUBBLEThe sort command has options to sort in reverse gild, ignore case when sorting, sort based upon multiple keys and a plethora of other options. A related filter, useful when combined with sort is the uniq filter.

FFLINTSTONE

MTHOMAS

WFLINTSTONE

sed

Some other filter essential to manipulating strings is the stream editor plan, sed. Mayhap the most common employ of sed is to substitute one cord (i.e. regular expression) with another string. Generic syntax for cord/pattern substitution is:

sed 'southward/original_string/new_string/' < input_file > output_file

Annotation when using sed as in a higher place, the input redirection operator (<) may or may non be used, beliefs in either case will be the same. Additionally, if no output redirection is specified, the output is directed by default to stdout.

A uncomplicated example of this is to substitute every occurance of the string UNIX with the cord Unix every bit follows (refer to preface for an explanation of why):

$ sed 's/UNIX/Unix/' input_file > output_file [Enter] The s directive to sed implies to substitute an occurance of the first string (UNIX) with the 2d string (Unix); receiving input from the file input_file and directing output to the file output_file. Annotation that sed never makes changes to the input file. If the input file is to be permanently changed, 1 should: 1) save the output from sed to a temporary file, 2) verify the temporary file has been modified as desired, and three) supersede the original file with the temporary file (using mv), demonstrated as follows:

$ sed 's/UNIX/Unix/' < input_file > temp_file [Enter] $ cat temp_file [Enter] # verify changes are correct $ mv temp_file input_file [Enter]

In full general, the sed control is non intended for the novice. In the higher up example, results might not be equally desired. My use of the phrase an occurance above should accept more accurately read the first occurance on a line. To substitute every occurance on a line, the sed global option (g) should be specified as follows:

$ sed 's/UNIX/Unix/yard' input_file > output_file [Enter] The clarification of sed here is not intended to be inclusive or in depth, and is mentioned for further reference. grep

And still another very powerful and useful filter is the grep 1 command. The grep command is used to search through files and impress lines matching a specified pattern to standard out. The generic (non-piped) form of grep is:

grep pattern file(s)Thus we tin can look for specific user entries in the /etc/passwd file as follows:

$ grep flint /etc/passwd [Enter] fflintstone:2Ux9znoiuSpL:518:531:Fred Flint:/home/fflintstone:/bin/ksh wflintstone:24qza6RiyBZf:519:531:Wilma Flint:/habitation/wflintstone:/bin/ksh Notice that ii lines were displayed by grep, both lines matching the blueprint "flintstone". Consider the following example: $ grep fred /etc/passwd [Enter] $In this example, no results are displayed because fred does not match Fred since grep is example sensitive (unless using the -i, ignore instance pick). The pattern can contain any of Unix's metacharacters to more precisely define the pattern. There is also a egrep (extended grep) command (or grep -e) which extends the design matching capability.

When using grep with pipes, the file argument is omitted since the input data is arriving via the pipe as follows:

$ cat /etc/passwd | grep flintstone [Enter] fflintstone:2Ux9znoiuSpL:518:531:Fred Flintstone:/dwelling/fflintstone:/bin/ksh wflintstone:24qza6RiyBZf:519:531:Wilma Flint:/abode/wflintstone:/bin/ksh While some search patterns using grep are straight forrard, others while actualization elementary are not. See an example here. 1 Although there are many explanations well-nigh what grep stands for, the proper noun came from an ed (an early editor program) command, specifically yard/regular-expression/p; where the thousand stands for global, the regular-expression was shortened to re, and the p stands for print. [Kernighan & Pike]

Command Summary

- cut - remove sections from each line in a file

- grep - (search for and) print lines matching a pattern

- sed - control to alter a text stream

- sort - sort lines of text files

- tr - translate characters

- uniq - remove indistinguishable lines from a sorted file

- wc - print the number of bytes, words, and lines in files

- pipe operator - graphic symbol ( | ) used to link the output of one command to the input of some other

- redirection - changing the flow of an input, output or mistake stream

©2019, Mark A. Thomas. All Rights Reserved.

rodriguezswitithe.blogspot.com

Source: https://homepages.uc.edu/~thomam/Intro_Unix_Text/IO_Redir_Pipes.html

0 Response to "C++ Read Text Files Unknown Name I/o Redirect"

Publicar un comentario